Artificial Intelligence will change the way we work. The EIB’s loans help SMEs and start-ups in Europe and beyond keep pace with the new emerging technologies. Read more about the EIB’s commitment to the digital innovation.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Investment Bank.

Download the essay

Find out more about Robert D. Atkinson.

© European Investment Bank 2018

Photos: © Getty Images. All rights reserved

Notes

[1] Robert. D. Atkinson, "The Past and Future of America’s Economy: Long Waves of Innovation that Power Cycles of Growth" , (Edward Elgar, 2006).

[2] Robert D. Atkinson, “Think Like an Enterprise: Why Nations Need Comprehensive Productivity Strategies”, (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, May 2016).

[3] Daniel Castro and Joshua New, “The Promise of Artificial Intelligence”, (Center for Data Innovation, October 2016).

[4] Irving Waldawksy-Berger, “‘Soft’ Artificial Intelligence Is Suddenly Everywhere”, (The Wall Street Journal, January 16, 2016).

[5] Ibidem.

[6] Robert D. Atkinson, “It’s Going to Kill Us!’ and Other Myths about the Future of Artificial Intelligence”, (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, June 2016).

[7] Daniel Bentley, “Why Ford Won’t Rush an Autonomous Car to Market", (Fortune, December 6, 2017).

[8] Rodney Brooks, “Robots, AI, and Other Stuff”, (Rodney Brooks Blog, January 1, 2018).

[9] Ibidem.

[10] Carlota Perez, "Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages", (Edward Elgar Pub: 2003).

[11] Robert D. Atkinson, “The Coming Transportation Revolution”, (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, October 2014).

[12] Klaus Schwab, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means, how to respond”, (World Economic Forum, January 14, 2016).

[13] Robert D. Atkinson, “50 years of Moore's law, but for how much longer?”, (The Hill, April 16, 2015).

[14] “Are Advancements in Computing Over? The Future of Moore’s Law”, (ITIF Event, November 21, 2013).

[15] Robert D. Atkinson, “False Alarmism: Technological Disruption and the U.S. Labor Market, 1850–2015”, (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, May 2017).

[16] Boston University School of Public Health, Behavioral Change Models, “Diffusion of Innovation Theory”, accessed January 1, 2018.

[17] Three percent growth per year leads to a doubling in 27 years.

[18] Robert D. Atkinson, “False Alarmism: Technological Disruption and the U.S. Labor Market, 1850–2015”, (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, May 2017).

[19] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), "Technology, Productivity and Job Creation: Best Policy Practices", (Paris: OECD, 1998), 9, accessed March 7, 2016.

[20] Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osbourne, “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?”, (Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford, Oxford, September 17, 2013).

[21] Ben Miller, “Automation Not So Automatic”, (The Innovation Files, September 20, 2013).

[22] OECD, “Automation and Independent Work in a Digital Economy”, (May 2016).

[23] James Manyika, Susan Lund, Michael Chui, Jacques Bughin, Jonathan Woetzel, Parul Batra, Ryan Ko, and Saurabh Sanghvi, “Jobs Lost, Jobs Gained: Workforce Transitions in a Time of Automation”, (McKinsey Global Institute, December 2017).

[24] Michael Chui, James Manyika, and Mehdi Miremadi, “Four Fundamentals of Workplace Automation”, (McKinsey & Company: November 2015).

[25] OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012) and Arntz, M. T. Gregory and U. Zierahn (2016), “The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis”, (OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 189, OECD Publishing, Paris).

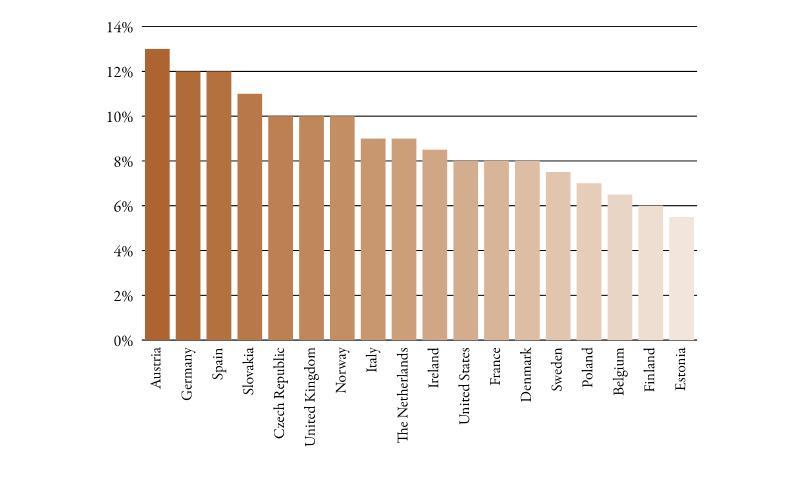

Note: Data for the United Kingdom corresponds to England and Northern Ireland. Data for Belgium corresponds to the Flemish Community.

[26] Executive Office of the President, “Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and the Economy”, accessed January 5, 2018.

[27] Melanie Arntz, Terry Gregory, Ulrich Zierahn, “The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis”, OECD Library, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, May 2016.

[28] One recent study found that over one-third of U.S. college graduates are overeducated in terms of the jobs they have, with similar numbers for EU nations. See Research working paper by Brian Clark and Arnaud Maurel from Duke University and Clément Joubert from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill titled “The Career Prospects of Overeducated Americans” using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 and Current Population Survey to look at overeducation’s effects on employment and wages over time. To analyze these effects, the researchers tracked almost 5,000 college graduates for 12 years after they entered the workforce. Their study shows that over one-third of college graduates are working in what the researchers call “overeducated employment”; https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/article/clayton.htm; https://www.bls.gov/osmr/abstract/ec/ec060110.htm.

[29] European Commission, Skills Panorama, “Skill Underutilization across Countries in 2014”.

[30] Manuel Trajtenberg, “AI as the next GPT: A Political-Economy Perspective”, (NBER Working Paper No. 24245, January 2018).

[31] Only 7.7 percent of U.S. high school students pass a statistics class, compared to approximately 87 percent for geometry.

[32] Betsy Brand, “High School Career Academies: A 40-Year Proven Model for Improving College and Career Readiness”, (American Youth Policy Forum, November 2009).

[33] Ministère du Travail, Mon Compte Formation, accessed January 7, 2018.

[34] LinkedIn, “Training Finder, Denver Colorado”, accessed January 7, 2018.

[35] Kevin J. Delaney, “The robot that takes your job should pay taxes, says Bill Gates”, (Quartz, February 17, 2017).

[36] Daniel Castro, “Digital Decision-Making: The Building Blocks of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence”, (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, December 2017).